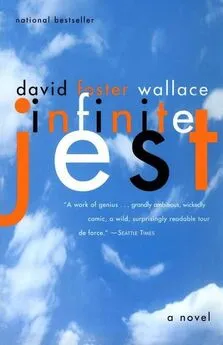

David Wallace - Infinite jest

- Название:Infinite jest

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Издательство:Back Bay Books

- Год:2006

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг:

- Избранное:Добавить в избранное

-

Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

David Wallace - Infinite jest краткое содержание

Infinite Jest is the name of a movie said to be so entertaining that anyone who watches it loses all desire to do anything but watch. People die happily, viewing it in endless repetition. The novel Infinite Jest is the story of this addictive entertainment, and in particular how it affects a Boston halfway house for recovering addicts and a nearby tennis academy, whose students have many budding addictions of their own. As the novel unfolds, various individuals, organisations, and governments vie to obtain the master copy of Infinite Jest for their own ends, and the denizens of the tennis school and halfway house are caught up in increasingly desperate efforts to control the movie — as is a cast including burglars, transvestite muggers, scam artists, medical professionals, pro football stars, bookies, drug addicts both active and recovering, film students, political assassins, and one of the most endearingly messed-up families ever captured in a novel.

On this outrageous frame hangs an exploration of essential questions about what entertainment is, and why it has come to so dominate our lives; about how our desire for entertainment interacts with our need to connect with other humans; and about what the pleasures we choose say about who we are. Equal parts philosophical quest and screwball comedy, Infinite Jest bends every rule of fiction without sacrificing for a moment its own entertainment value. The huge cast and multilevel narrative serve a story that accelerates to a breathtaking, heartbreaking, unfogettable conclusion. It is an exuberant, uniquely American exploration of the passions that make us human and one of those rare books that renew the very idea of what a novel can do.

Infinite jest - читать онлайн бесплатно полную версию (весь текст целиком)

Интервал:

Закладка:

He and Lenz have become separated, he realizes. Now way southwest of Union on Comm., Green looks around at traffic and T-tracks and bar-patrons and T.U.L.’s huge bottle’s low-neon flutter. He wonders whether he’s somehow blown Lenz off or whether Lenz’s blown him off, and that’s all he wonders, that’s the total complexity the speculation assumes, that’s his thought for the minute. It’s like the whole nut-can-and-cigar traumas drained into some psychic sump at puberty, sank and left only an oily slick that catches the light in distorted ways. The warbly Polynesian music’s way clearer up here. He starts up the steep hill on Brainerd Rd., which terminates at the Enfield line. Maybe Lenz can’t move straightforwardly south at all past a certain time. The acclivity is not kind to asphalt-spreader’s boots. After the initial crazed-gerbil-in-brain phase of early Withdrawal and detox, Bruce Green has now returned to his normal psychorepressed cerebral state where he has about one fully developed thought every sixty seconds, and then just one at a time, a thought, each materializing already fully developed and sitting there and then melting back away like a languid liquid-crystal display. His Ennet House counselor, the extremely tough-loving Calvin T., complains that listening to Green is like listening to a faucet with a very slow drip. His rap is that Green seems not serene or detached but totally shut down, disassociated, and Calvin T. tries weekly to draw Green out by pissing him off. Green’s next full thought is the realization that even though the hideous Hawaiian music had sounded like it was drifting up northward from down at the Allston Spur, it’s somewhat louder now the farther west he moves toward Enfield’s Cambridge St. dogleg and St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Brainerd between Commonwealth and Cambridge St. is a sine wave of lung-busting hills through neighborhoods Tiny Ewell had described as Depressed Residential, unending rows of crammed-together triple-decker houses with those tiny sad architectural differences that seem to highlight the essential sameness, with sagging porches and psoriatic paint-jobs or aluminum siding gone carbuncular from violent temperature-swings, yard-litter and dishes and patchy grass and fenced pets and children’s toys lying around in discarded attitudes and eclectic food-smells and wildly different-patterned curtains or blinds in a house’s different windows due to these old houses are carved up inside into apartments for like alienated B.U. students or Canadian and Concavity-displaced families or even more alienated B.C. students, or probably it looks like the bulk of the lease-holders are Green-and-Bonkesque younger blue-collar hard-partying types that have posters of the Fiends In Human Shape or Choosy Mothers or Snout or the Bioavaílable Five [241]in the bathroom and black lights in the bedroom and oil-change stains in the driveway and that throw their supper dishes into the yard and buy new dishes at Caldor instead of washing their dishes and that still, in their twenties, ingest Substances nightly and use party as a verb and put their sound-systems’ speakers in their apartments’ windows facing out and crank the volume out of sheer high-spirit obnoxiousness because they still have their girlfriends to pound beers with and do shotguns of dope into the mouth of and do lines of Bing off various parts of the naked body of, and still find pounding beers and doing bongs and lines fun and get to have fun on a nightly after-work basis, cranking the tunes out into the neighborhood air. The street’s bare trees are densely limbed, they’re a certain type of tree, they look like inverted brooms in the residential dark, Green doesn’t know his tree-names. The Hawaiian music is what’s pulled him southwest, it emerges: it’s originating from someplace in this very neighborhood somewhere around W. Brainerd, and Green moves upriver toward what sounds like the source of the sound with a blankly horrified fascination. Most of the yards are fenced in stainless-steel chain-link fencing, and occasional yard-dogs whine or more commonly bark and snarl and leap territorially at Green from behind their fences, the fences shivering from the impact and the chain-link stuff dented outward from previous impacts from previous passersby. The thought that he isn’t scared of dogs develops and recedes in Green’s midbrain. His jacket creaks with every step. The temperature is steadily dropping. The fenced front yards are the toy-and-beer-can-strewn type where the brown grass grows in uneven tufts and the leaves haven’t been raked and are piled in wind-blown lines of force along the base of the fence and unpruned hedges and overfull wastebaskets and untwisted trash-bags are on the sagging porch because nobody’s gotten around to taking them down to the E.W.D. dumpster at the corner and garbage from the overfull receptacles blows out into the yard and mixes with the leaves along the fences’ base and some gets out into the street and is never picked up and eventually becomes part of the composition of the street. A nonpeanut M&M box is like intaglioed into the concrete of the sidewalk under Green, so bleached by the elements it’s turned bone-white and is only barely identifiable as a nonpeanut M&M box, for instance. And, looking up from identifying the M&M box’s make, Green now espies Randy Lenz. Green has happened upon Lenz, way up here on Brainerd, now strolling briskly alone up ahead of Green, not close but visible under a functioning streetlight about a block farther uphill on Brainerd. There’s some disincentive to call out. The incline on this block isn’t bad. It’s cold enough now so his breath looks the same whether he’s smoking or not. The tall curved streetlamps here look to Green just like the weaponish part of the Martian vessels that fired fatal rays in their conquest of the planet in an ancient cartridge Tommy Doocy’d never tired of that he labelled the case ‘War of the Welles.’ The Hawaiian music dominates the aural landscape by this point, now, coming from someplace up near where he sees the back of Lenz’s coat. Someone has put Polynesian-music speakers in their window, pretty clearly. Creepy slack-key steel guitar balloons across the dim street, booms off the sagging facades opposite, it’s Don Ho and the Sol Hoopi Players, the grass-skirt-and-foamy-breakers sound that makes Green put his fingers in his ears while at the same time he moves more urgently toward the Hawaiian-music source, a pink or aqua three-decker with a second-floor dormer and red-shingled roof with a blue and white Quenucker flag on a pole protruding from a window in the dormer and serious JBL speakers facing outward in the two windows on either side of the flag, with the screens off so you can see the woofers throbbing like brown bellies hula-ing, bathing the 1700 block of W. Brainerd in dreadful ukuleles and hollow-log percussives. All the blunt fingers in his ears do is add the squeak of Green’s pulse and the underwater sound of his respiration to the music, though. Figures in plaid-flannel or else floral Hawaiian shirts and those flower necklaces melt in and out of lit view behind and over the window-speakers with the oozing quality of large-group chemical fun and dancing and social intercoursing. The lit windows make slender rectangles of light out across the yard, which the yard is a sty. Something about Randy Lenz’s movements up ahead, the high-kneed tiptoed skulk of a vaudeville fiend up to no good at all, keeps Green from calling out to him even if he could have made himself heard over what to him is a roar of blood and breath and Ho. Lenz moves through the one operative streetlight’s cone across the sidewalk and over to the stainless chain-link of the same Que-nucker house, holding something out to a Shetland-sized dog whose leash is attached to a fluorescent-plastic clothesliney thing by a pulley, and can slide. It’s cold and the air is thin and keen and his fingers are icy in his ears, which ache with cold. Green watches, rapt on levels he doesn’t know he has, drawn slowly forward, moving his head from side to side to keep from losing Lenz in the fog of his breath, not calling out, but transfixed. Green and Mildred Bonk and the other couple they’d shared a trailer with T. Doocy with had gone through a phase one time where they’d crash various collegiate parties and mix with the upper-scale collegiates, and once in one February Green found himself at a Harvard U. dorm where they were having a like Beach-Theme Party, with a dumptruck’s worth of sand on the common-room floor and everybody with flower necklaces and skin bronzed with cream or UV-booth-salon visits, all the towheaded guys in floral untucked shirts walking around with lockjawed noblest oblige and drinking drinks with umbrellas in them or else wearing Speedos with no shirts and not one fucking pimple anyplace on their back and pretending to surf on a surfboard somebody had nailed to a hump-shaped wave made of blue and white papier mâché with a motor inside that made the fake wave sort of undulate, and all the girls in grass skirts oozing around the room trying to hula in a shimmying way that showed their thighs’ LipoVac scars through the shimmying grass of their skirts, and Mildred Bonk had donned a grass skirt and bikini-top out of the pile by the keggers and even though almost seven months pregnant had oozed and shimmied right into the mainstream of the swing of things, but Bruce Green had felt awkward and out of place in his cheap leather jacket and haircut he’d dyed orange with gasoline in a blackout and the EAT THE RICH patch he’d perversely let Mildred Bonk sew onto the groin of his police-pants, and then they’d finally got tired of the ‘Hawaii Five-0’ theme and started in with the Don Ho and Sol Hoopi CDs, and Green had gotten so uncomfortably fascinated and repelled and paralyzed by the Polynesian tunes that he’d set up a cabana-chair right by the kegs and had sat there overworking the pump on the kegs and downing one plastic cup after another of beer-foam until he got so blind drunk his sphincter had failed and he’d not only pissed but also actually shit his pants, for only the second time ever, and the first public time ever, and was mortified with complexly layered shame, and had to ease very gingerly into the nearest-by head and remove his pants and wipe himself off like a fucking baby, having to shut one eye to make sure which him he saw was him, and then there’d been nothing to do with the fouled police-pants but crack the bathroom door and reach a tattooed arm out with the pants and bury them in the living room’s sand like a housecat’s litterbox, and then of course what was he supposed to put on if he ever wanted to leave that head or dorm again, to get home, so he’d had to hold one eye shut and reach one arm out again and like strain to reach the pile of grass skirts and bikini-tops and snatch a grass skirt, and put it on, and slip out of the Hawaiian dorm out a side door without letting anybody see him, and then ride the Red Line and C-Greenie and then a bus all the way home in February in a cheap leather jacket and asphalt-spreader’s boots and a grass skirt, the grass of which rode up in the most horrifying way, and he’d spent the next three days not leaving the trailer in the Spur, in a paralyzing depression of unknown etiology, lying on Tommy D.’s crusty-stained sofa and drinking Southern Comfort straight out of the bottle and watching Doocy’s snakes not move once in three days, in their tank, and Mildred had given him two days of high-volume shit for first sulking antisocially by the keg and then screwing out and abandoning her at seven months gone to a sandy room full of tanly anomic blondes who said catty things about her tattoos and creepy boys who talked without moving their lower jaw and asked her things like where she ‘summered’ and kept offering her advice on no-load funds and inviting her upstairs to check out their Dürer prints and saying they found overweight girls terribly compelling in their defiance of culturo-ascetic norms, and Bruce Green lay there with a head full of Hoopi and unresolved pain and didn’t say a word or even have a fully developed thought for three days, and had hidden the grass skirt under the dustruffle of the couch and later savagely torn it to shreds and sprinkled the clippings over Doocy’s hydroponic-marijuana development in the tub, for mulch. Lenz goes in and out of Green’s focus several times within a dozen andante strides, still out in front of the Canadian-refugee-type house that’s drawn Green on, Lenz holding a little can of something up over one side of the fence’s gate and dribbling something onto the gate, holding something else that suddenly engages the dog’s full attention. For some reason Green thinks to check his watch. The pink or orange clothesline quivers as the leash’s pulley runs along it as the dog comes up to meet Lenz inside the gate he’s slowly opened. The huge dog seems neither friendly nor unfriendly toward Lenz, but his attention is engaged. The leash and pulley could never hold him if he decided Lenz was food. There’s bitter-smelling material from his ear on Green’s finger, which he can’t help but sniff. He’s forgotten and left the other finger in his ear. He’s now pretty close, standing in a van’s shadow just outside the pyramid of sodium light from the streetlight, like two houses down from the source of the grisly sound, which all of a sudden is in the silence between cuts of Ho’s early Don Ho: From Hawaii With All My Love, so that Green can hear baritone Canadianese party-voices through the open windows and also the low lalations of baby-talk of some sort from Lenz, ‘Pooty ooty doggy woggy’ and whatnot, presumably directed at the dog, who’s coming over to Lenz in a sort of neutrally cautious but attentive way. Green has no clue what kind of dog it is, but it’s big. Green can remember not the sight but the two very different sounds of the footfalls of his Pop the late Mr. Green pacing the Waltham living room, the crinkle of the paper bag around the tallboy in his hand. It’s well after 2245h. The dog’s leash slides hissing to the end of the Day-Glo line and stops the dog a couple paces from the inside of the gate, where Lenz is standing, inclined in the slight forward way of somebody who’s talking baby-talk to a dog. Green can see that Lenz has a slightly gnawed square of Don G.’s hard old meatloaf out in front of him, holding it toward the straining dog. Lenz has the blankly intent look of a short-haired man with a Geiger counter. The hideously compelling Ho starts again with the total abruptness that makes CDs so creepy. Green’s got one finger in one ear, shifting around slightly to keep Lenz’s lampshadow from blocking the view. The music balloons and booms. The Nucks have turned it way up for ‘My Lovely Launa-Una Luau Lady,’ a song that’s always made Green want to put his head through a window. Part of the in-strumentals sounds like a harp on acid. The hollow-log percussives are like a heart in your extremest-type terror. Green fancies he can see windows in the houses opposite vibrate from the horrific vibration. Green’s having way more than one thought p.m. now, the squeak of the gerbil-wheel starting to crank deep inside. The undulating shiver is a slack-steel guitar that fills little Brucie’s head with white sand and undulating tummies and heads that resemble New Year’s subsidized parade balloons, huge soft shiny baggy wrinkled grinning heads nodding and bobbing as they slowly inflate to the shape of a giant head, tilted forward, straining at the ropes they’re pulled by. Green hasn’t watched a New Year’s parade since the Year of the Tucks Medicated Pad’s, which had been obscene. Green’s close enough to see that the Hawaiianized Nuck house is 412 W. Brainerd. Blue-collar-type cars and 4x4s and vans are all up and down the street packed in in a somehow partyish attitude, as in parked in a hurry, some of them with Canadian lettering on the plates. Fleur-de-lis stickers and slogans in Canadian on some of the windows also. An old Montego cammed out into a slingshot dragster is parked square in front of 412 in a sort of menacing way with two wheels up on the curb and a circle of flowers hung jauntily over the antenna, and the ellipses of dull fade in the paintjob of the hood that show the engine’s been bored out and the hood gets real hot, and Lenz has gotten down on one knee and breaks off some of the meatloaf and tosses it underhand to the ground inside the leash’s range. The dog goes over and lowers its head to the meat. The distinctive sound of Gately’s meatloaf getting chewed plus the ghastly music’s zithery warbling roar. Lenz now rises and his movements in the yard have a melting and wraithlike quality in the different shades of shadow. The lit window farthest from the limp flag has solid swarthy guys in beards and loud shirts passing back and forth snapping their fingers under their elbows with flower-strewn females in tow. Many of the heads are thrown back and attached to Molson bottles. Green’s jacket creaks as he tries to breathe. The snake had leapt from the can with a sound like: spronnnnng. His aunt at the Winchester breakfast nook, in dazzling winter dawnlight, quietly doing a word-search puzzle. Two dormer windows are half-blocked by the throbbing rectangles of the JBLs. Green’s the type that can recognize a JBL speaker and Molson-green bottle from way far away.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка: