Richard Bandler - Using Your Brain —for a CHANGE

- Название:Using Your Brain —for a CHANGE

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Издательство:Real People Press

- Год:1985

- Город:Moab, Utah

- ISBN:0–911226–26–5

- Рейтинг:

- Избранное:Добавить в избранное

-

Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Richard Bandler - Using Your Brain —for a CHANGE краткое содержание

Bandler is an innovator and an original thinker in the field of psychology. This book is a transcript of Bandler live in front of an audience, cutting up and cracking jokes as he is prone to do, talking about some of his unique and often practical views on how you can change your feelings, thoughts and behavior. Change is often easier than you think if you use the right method.

Using Your Brain —for a CHANGE - читать онлайн бесплатно полную версию (весь текст целиком)

Интервал:

Закладка:

Most of you learned a model of the atom that said there is a nucleus made up of protons and neutrons, with electrons flying around the outside like little planets. Niels Bohr got the Nobel prize for that description back in the 1920's. Over a period of about 50 years that model was the basis for an immense number of discoveries and inventions, such as the plastic in those Naugahyde chairs you're sitting on.

Fairly recently, physicists decided that Bohr's description of the atom is wrong. I wondered if they were going to take back his Nobel prize, but then I found out Bohr is dead, and he already spent the money. The really amazing thing is that all the discoveries that were made by using a "wrong" model are still here. The Naugahyde chairs didn't disappear when physicists changed their minds. Physics is usually presented as a very "objective" science, but I notice that physics changes and the world stays the same, so there must be something subjective about physics.

Einstein was one of my childhood heroes. He reduced physics to what psychologists call "guided fantasy," but which Einstein referred to as a "thought experiment." He visualized what it would be like to ride on the end of a beam of light. And people say that he was academic and objective! One of the results of this particular thought experiment was his famous theory of relativity.

NLP differs only in that we deliberately make up lies, in order to try to understand the subjective experience of a human being. When you study subjectivity, there's no use trying to be objective. So let's get down to some subjective experience. . . .

II. Running Your Own Brain

I'd like you to try some very simple experiments, to teach you a little bit about how you can learn to run your own brain. You will need this experience to understand the rest of this book, so I recommend that you actually do the following brief experiments.

Think of a past experience that was very pleasant — perhaps one that you haven't thought about in a long time. Pause for a moment to go back to that memory, and be sure that you see what you saw at the time that pleasant event happened. You can close your eyes if that makes it easier to do. ...

As you look at that pleasant memory, I want you to change the brightness of the image, and notice how your feelings change in response. First make it brighter and brighter. . . . Now make it dimmer and dimmer, until you can barely see it. ... Now make it brighter again.

How does that change the way you feel? There are always exceptions, but for most of you, when you make the picture lighter, your feelings will become stronger. Increasing brightness usually increases the intensity of feelings, and decreasing brightness usually decreases the intensity of feelings. How many of you ever thought about the possibility of intentionally varying the brightness of an internal image in order to feel different? Most of you just let your brain randomly show you any picture it wants, and you feel good or bad in response.

Now think of an unpleasant memory, something you think about that makes you feel bad. Now make the picture dimmer and dimmer. ... If you turn the brightness down far enough it won't bother you any more. You can save yourself thousands of dollars in psychotherapy bills.

I learned these things from people who did them already One woman told me that she was happy all the time; she didn't let things get to her. I asked her how she did it, and she said "Well, those unpleasant thoughts come into my mind, but I just turn the brightness down."

Brightness is one of the "submodalities" of the visual modality. Submodalities are universal elements that can be used to change any visual image, no matter what the content is. The auditory and kinesthetic modalities also have submodalities, but for now we'll play with the visual submodalities.

Brightness is only one of many things you can vary. Before we go on to others, I want to talk about the exceptions to the impact brightness usually has. If you make a picture so bright that it washes out the details and becomes almost white, that will reduce, rather than increase, the intensity of your feelings. Usually the relationship doesn't hold at the upper extreme. For some people, the relationship is reversed in most contexts, so that increasing brightness decreases the intensity of their feelings.

Some exceptions are related to the content. If your pleasant picture is candlelight, or twilight, or sunset, part of its special charm is due to the dimness; if you brighten the image, your feelings may decrease. On the other hand, if you recalled a time when you were afraid in the dark, the fear may be due to not being able to see what's there. If you brighten that image and see that there's nothing there, your fear will decrease, rather than increase. So there are always exceptions, and when you examine them, the exceptions make sense, too. Whatever the relationship is, you can use that information to change your experience.

Now let's play with another submodality variable. Pick another pleasant memory and vary the size of the picture. First make it bigger and bigger, . . . and then smaller and smaller, noticing how your feelings change in response. . . .

The usual relationship is that a bigger picture intensifies your response, and a smaller picture diminishes it. Again there are exceptions, particularly at the upper end of the scale. When a picture gets very large, it may suddenly seem ridiculous or unreal. Your response may then change in quality instead of intensity — from pleasure to laughter, for instance.

If you change the size of an unpleasant picture, you will probably find that making it smaller also decreases your feelings. If making it really big makes it ridiculous and laughable, then you can also use that to feel better. Try it. Find out what works for you.

It doesn't matter what the relationship is, as long as you find out how it works for your brain so that you can learn to control your experience. If you think about it, none of this should be at all surprising. People talk about a "dim future" or "bright prospects." "Everything looks black." "My mind went blank." "It's a small thing, but she blows it all out of proportion." When someone says something like that, it's not metaphorical; it's usually a literal and precise description of what that person is experiencing inside.

If someone is "blowing something out of proportion," you can tell her to shrink that picture down. If she sees a "dim future," have her brighten it up. It sounds simple, . . . and it is.

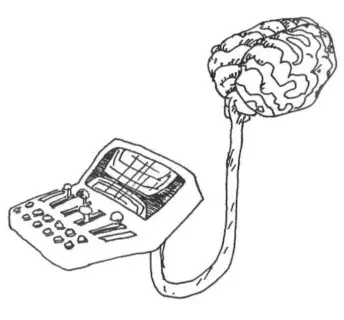

There are all these things inside your mind that you never thought of playing with. You don't want to go messing around with your head, right? Let other people do it instead. All the things that go on in your mind affect you, and they are all potentially within your control. The question is, "Who's going to run your brain?"

Next I want you to go on to experiment with varying other visual elements, to find out how you can consciously change them to affect your response. I want you to have a personal experiential understanding of how you can control your experience. If you actually pause and try changing the variables on the list below, you will have a solid basis for understanding the rest of this book. If you think you don't have the time, put this book down, go to the back of the bus, and read some comic books or the National Enquirer instead.

For those of you who really want to learn to run your own brain, take any experience and try changing each of the visual elements listed below. Do the same thing you did with brightness and size: try going in one direction . . . and then the other to find out how it changes your experience. To really find out how the your brain works, change only one element at a time. If you change two or more things at the same time, you won't know which one is affecting your experience, or how much. I recommend doing this with a pleasant experience.

1. Color. Vary the intensity of color from intense bright colors to black and white.

2. Distance. Change from very close to far away.

3. Depth. Vary the picture from a flat, two–dimensional photo to the full depth of three dimensions.

4. Duration. Vary from a quick, fleeting appearance to a persistent image that stays for some time,

5. Clarity. Change the picture from crystal–clear clarity of detail to fuzzy indistinctness.

6. Contrast. Adjust the difference between light and dark, from stark contrast to more continuous gradations of gray.

7. Scope. Vary from a bounded picture within a frame to a panoramic picture that continues around behind your head, so that if you turn your head, you can see more of it.

8. Movement, Change the picture from a still photo or slide to a movie.

9. Speed. Adjust the speed of the movie from very slow to very fast.

10. Hue. Change the color balance. Increase the intensity of reds and decrease the blues and greens, for example.

11. Transparency. Make the image transparent, so that you can see what's beneath the surface.

12. Aspect Ratio. Make a framed picture tall and narrow . . . and then short and wide.

13. Orientation. Tilt the top of that picture away from you . . . and then toward you.

14. Foreground/background. Vary the difference or separation between foreground (what interests you most) and background (the context that just happens to be there). . . . Then try reversing it, so the background becomes interesting foreground. (For more variables to try, see Appendix I)

Now most of you should have an experience of a few of the many ways you can change your experience by changing submodalities. Whenever you find an element that works really well, take a moment to figure out where and when you'd like to use it. For instance, pick a scary memory — even something from a movie. Take that picture and make it very large very suddenly. . . . That one's a thrill. If you have trouble getting going in the morning, try that instead of coffee!

I asked you to try these one at a time so that you could find out how they work. Once you know how they work, you can combine them to get even more intense changes. For example, pause and find an exquisitely pleasant sensual memory. First, make sure that it's a movie rather than just a still slide. Now take that image and pull it closer to you. As it comes closer, make it brighter and more colorful at the same time that you slow the movie to about half speed. Since you have already learned something about how your brain works, do whatever else works best to intensify that experience for you. Go ahead. . . .

Do you feel different? You can do that anytime ... and you will have already paid for it. When you're just about to be really mean to someone you love, you could stop and do this. And with the look that's on your faces right now, who knows what you could get into . . . .all kinds of fun trouble!

What's amazing to me is that some people do it exactly backwards. Think what your life would be like if you remembered all your good experiences as dim, distant, fuzzy, black and white snapshots, but recalled all your bad experiences in vividly colorful close, panoramic, 3–D movies. That's a great way to get depressed and think that life isn't worth living. All of us have good and bad experiences; how we recall them is often what makes the difference.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка: